McComas Taylor

Australian National University

Someone once told me that the fastest way to a Dutchman’s heart was with Speculaas biscuits. Clutching a packet of those spicy treats, I nervously approached the front door of the irascible Professor JW de Jong (1921-2000). I had begun my doctoral research at the Australian National University just a few years before he died and I had decided to pay a courtesy call to the noted Indologist and Buddhist Studies scholar at his home in a leafy suburb of Canberra.

Mrs de Jong welcomed me in, and the three of us had tea and biscuits in their airy front room with big picture windows looking over the garden. The biscuits apparently worked their magic: instead of the daunting figure I had feared, I found a diminutive scholarly gentleman with big hair and thick glasses. I don’t remember the details of our conversations, but after tea, Prof. de Jong led the way down through a gallery packed with books on either side to his library/studio in a converted garage in the back garden.

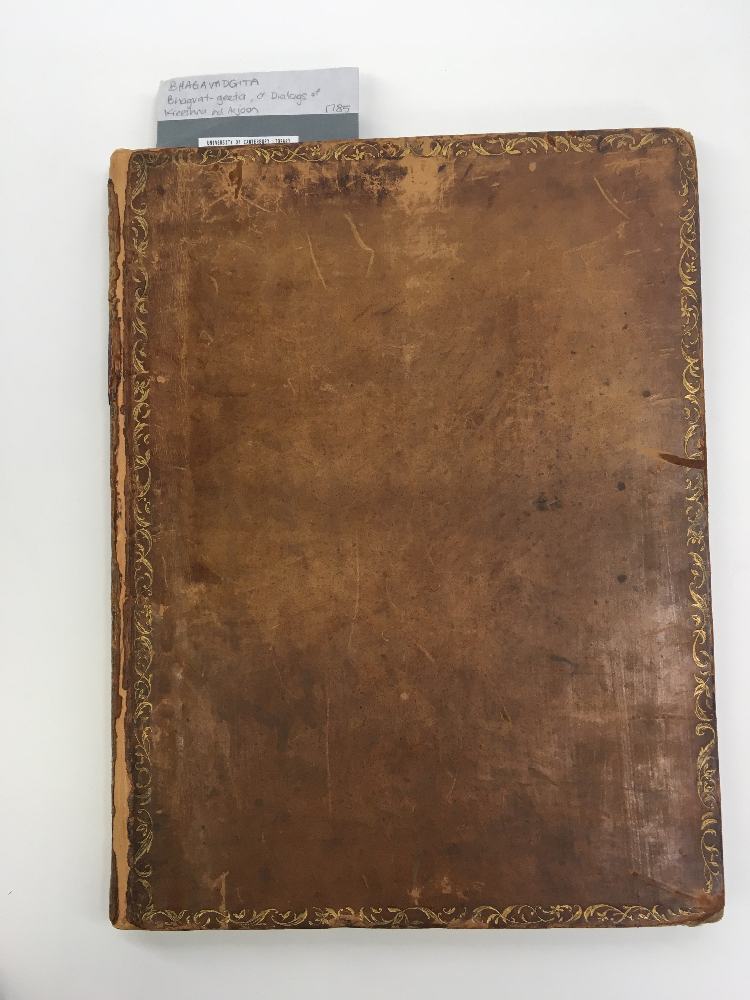

From a shelf he drew out one of the prizes of his 14,000-volume collection: a large brown book of obvious antiquity. De Jong proudly opened the book and showed me the title page: The Bhăgvăt-Gēētā or Dialogues of Krĕĕshnă and Ărjŏŏn. I drew my breath. This is one of the holy grails of Indology and arguably one of the most influential books in the world, Charles Wilkins’ 1785 translation of the Hindu classic, the Bhagavadgītā.

Wilkins himself was an interesting character. Born in England in 1749, he trained not in a scholarly or intellectual discipline, but as a printer. Like many adventurous young men of his generation he was lured to India where fabulous fortunes or sudden death were equally possible. Reaching Calcutta in 1770 he worked as printer for the East India Company and elevated himself through the system, mastering Persian, Bengali and Sanskrit on the way. With the great British orientalist William Jones, Wilkins co-founded the Asiatick Society of Bengal, the first scholarly organisation dedicated to the study of the Indic cultural world. Wilkins he returned to England in 1786, the year after his translation appeared, and died there many years later at the ripe old age of 86.

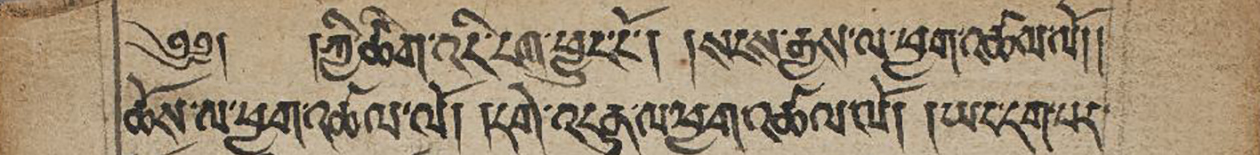

Written in Sanskrit about two millennia ago, 700-verse Bhagavadgītā appears in the middle of the great Indian epic, the Mahābhārata. A great internecine war between two rival branches of the royal family is about to begin. When the two armies have arrayed themselves for battle, Arjuna, one of the leading warriors, losses his nerve and refuses to fight against an army consisting mainly of this kinsmen and mentors. He turns to his charioteer Kṛṣṇa (Krishna) for advice, but gets much more than he bargained for. Not only does Kṛṣṇa give solace to the hapless hero, he reveals himself to be supreme deity in human form, and teaches Arjuna about the illusory nature of existence. Thus chastened, Arjuna regains his composure and the battle begins.

Over the centuries, the Bhagavadgītā, or ‘Song of the Lord’ as it is sometimes translated, has been sung, cited, recited, illustrated and annotated across the length and breadth of India. It is one of the best loved texts in the Hindu world, not only is it written in beautiful poetic form, it is a source of profound philosophy and insight.

Wilkins’ translation (which he undertook with the unacknowledged assistance of a pandit, Kasinatha Bhattacharya) brought this remarkable text to a European audience for the first time, where it caused a sensation. Romantics loved it because its monotheistic tone suggested that Indians were ‘just like us’, as they believed in a single ‘God’. Orientalists loved it as it fed into the concept of a mysterious, spiritual ‘East’. Indian nationalists, including Gandhi himself, confronted by monolithic religions like Christianity and who needed to establish a unified image of ‘Hinduism’, found in the Gītā a convenient ‘Hindu Bible’.

In the West, the Gītā was for many people the first point of contact with India, and sparked an interest, a love or a fascination for that land and its people. It has been the entry point for many to Hindu traditions, to India, and to Indian studies. This text has shaped perceptions of India in the West, and indeed throughout Asia, down the generations.

Wilkin’s first work effectively spawned an entire Gītā translations industry. Richard H. Davis, author of The Bhagavadgita: A Biography, cites earlier work by Callewaert and Hemraj who identified 1891 translations of the text into 75 languages. Davis estimates there are now well over 300 English translations alone.

After de Jong’s death in the year 2000, the University of Canterbury acquired his entire library and fifty lineal meters of manuscripts from his widow. The collection is now in the care of the Macmillan Brown Library. At a recent workshop organized by Dr Clemency Montelle to celebrate the de Jong archive, I had the pleasure of encountering this rare volume again, after an interval of nearly twenty years.

Joanna Condon, who manages the collection, had laid out a number of collection’s treasures for us to enjoy in the rare books room. Each volume lay open in a white pillow to avoid damaging the spine. Wilkins’ Gēētā was larger than I remember – officially it is quarto, which is about the size of a modern A4 sheet. Its brown board cover shows its age, but the pages are surprisingly crisp and bright, and look like they were printed yesterday. Nice to know that this extraordinary treasure will be safe for generations of scholars to consult and to enjoy from now on.

Congratulations! May I suggest a trifle of a correction?

In the title, Wilkin’s ought to be Wilkins’, as is correctly done in the text.

Thanks – noted and corrected.