We have discussed the microbiome on our blog before, and the important impacts that the microbiome has on our health and wellbeing. However, what do you do when you feel that your microbiome needs a boost? It is possible to change your microbiome, for both better and worse?

In this blog we will discuss a number of ways that we can improve your microbiome by increasing the diversity of bacteria in your gut, which in turn may improve your health and wellbeing.

The importance of the human gut microbiome

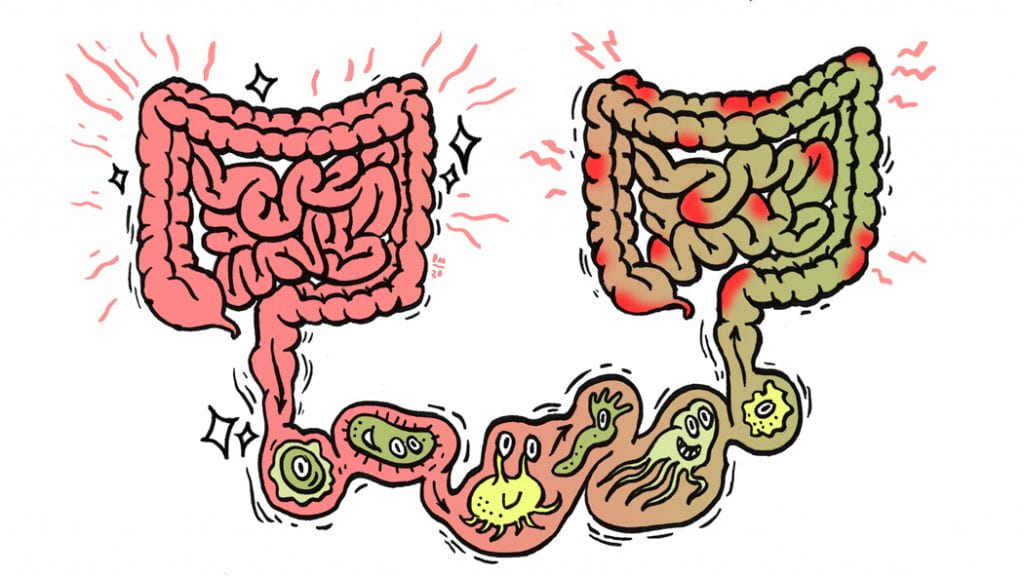

The human gut microbiome is made up of tens of trillions of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses1. Research is finding that our microbiome can have significant impacts on our physical and mental health. Though research on ‘good’ and ‘bad’ bacteria is still in its infancy, it is becoming clear that greater bacterial diversity is probably linked with optimal health.

Altering the gut microbiome

The gut microbiome can be seen as a garden that needs tending. We can cultivate the plants that we already have in our garden as well as adding new plants. The diversity of the gut microbiome can be increased in a number of ways. This includes increasing the amount of fresh food in our meals; the greater the variety of fresh foods we eat, the greater the variety of bacteria in our guts2. Fresh foods add naturally occurring bacteria to our guts as well as feeding our existing bacteria. By trying out a new fruit or vegetable we can add new plants to our inner garden. Further, diets high in processed foods (often referred to as the Western diet) lower the diversity of gut bacteria, and this reduction in diversity may cause cravings for processed foods, thus creating a negative cycle2 3.

Another way to tend our microbiome is by consuming probiotics (beneficial bacteria) which temporarily add bacterial diversity to our guts1 4 5. This is like adding new plants to our inner garden. Probiotics can be found in capsule form as well as in some foods. Foods high in probiotics include natural yoghurt, lactic acid fermented vegetables such as sauerkraut and kimchi, as well as fermented beverages such as kombucha, kefir and kvass.

Adding new plants is great, but it is also important to tend to the plants that are already in our inner gardens. We can do this by eating prebiotics (indigestible fibre), which act as fertiliser to feed our existing bacteria. Fresh fruits and vegetables, including legumes, green leafy vegetables and seaweed are great sources of prebiotics.

Another intriguing and new method of altering the composition of the gut microbiome is through a microbiota transplant. Transplantation is like having an inner garden renovation. These transplants aim to replace or replenish diversity of bacteria in the gut. This transplantation process is known by many names, but for this post we will use the term microbiota transfer therapy or MTT.

Microbiota Transfer Therapy process

MTT involves collecting bacteria from stools of healthy donors (people free of diseases and infections to prevent spreading illness). Once this bacteria has been collected, it is administered orally (through nasogastric tubes, liquid drinks or capsules) or via the rectum (through enemas or colonoscopies).

Who even thought of microbiota transfers?

MTT has a very long history. The first recorded use was by Ge Hong, a Chinese physician in the 4th Century, to treat patients suffering from severe diarrhoea6.

However, there is virtually no record of MTT being used until the late 1950s when it was used as a last resort to treat four patients that were suffering from severe Clostridium difficile (C. diff) infection at Denver Hospital and were expected not to survive7. However, within 24 hours all four patients had completely recovered. Today MTT is a standard treatment for recurrent C. diff infection.

In recent times, claims have been made by both physicians and patients that MTT has treated or even reversed a variety of physical and psychiatric conditions including bipolar disorder, depression, Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease, and type 2 diabetes. However, rigorous scientific testing for MTT as a treatment for conditions other than C. diff is limited.

Microbiota transfer in nature

Although MTT seems like an extreme measure, exchanging of gut bacteria is seen in some animals. Some animal species, including koalas, hippos, pandas and elephants are born with little or no bacteria in their gut, and they consume their mother’s faeces shortly after birth which populates their gut with bacteria8-10. Gut bacteria are vital for these animals to breakdown the large amount of leaves and grass that they eat.

Human babies also consume their mother’s bacteria. In humans this occurs not through eating faeces but through breast milk. Human breast milk contains over 700 different types of bacteria, which are important for the development of the infants’ microbiome. Infants who are predominantly breastfed have differences in their microbiome than those who are not predominately breastfed11.

Microbiota Transfer Therapy and mental health

Case studies have been published on the effectiveness of MTT for treating psychiatric illness in humans. These studies include anorexia nervosa and severe depression. MTT was successful at treating symptoms of anorexia nervosa (AN) in a 26 year old female after psychiatric treatment had been unsuccessful12. Additionally, MTT was reported to have remitted symptoms of severe depression in a 79 year old female after antidepressant medication was unsuccessful13. The diversity of the gut bacteria was measured before MTT and at follow-up time points, and for both of these patients bacterial diversity was significantly increased after MTT12 13.

These two case studies show that MTT has resulted in improvements; however, we need to keep in mind that each study focused on only one individual. As such, we cannot say that MTT is an effective treatment for these conditions as other factors may have influenced their improvement. To date only two rigorous studies have been published on the use of MTT as a potential treatment for mental health symptoms; childhood autism14 and adults with depression and anxiety15.

Autism Spectrum Disorder in children

MTT was used with success at treating symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)14 16. This study recruited 18 children with ASD, aged 7-17 years. Prior to MTT being given, the children with ASD had significantly lower diversity of gut bacteria than neuro-typical children.

GI symptom improvement

All of these children had experienced chronic gastro-intestinal (GI) symptoms since infancy, such as chronic diarrhoea or constipation. Eight weeks after MTT, GI problems were significantly reduced. Incredibly, these GI improvements continued even two years after treatment.

ASD symptom and severity improvement

After MTT, ASD symptoms and severity were significantly improved as measured by both parents and clinical professions. These improvements were seen 8 weeks after MTT, but continued to significantly improve 2 years after treatment.

Though this study found significant and important improvements for children with ASD, it is essential that we keep in mind that the study had a number of limitations. It had a small sample size, meaning that we need to take care when generalising it to all children with ASD. Additionally, this study used an open-label design (that is all children and their parents knew that they were receiving MTT with no placebo used), which means that placebo effects may be present.

Microbiota Transfer Therapy and depression and anxiety

MTT has been shown to improve symptoms of anxiety and depression15. A study treated 17 adults with GI symptoms (including 12 with depression and 5 with anxiety). Four weeks after MTT, 50% of those with depression and 60% with anxiety reported significant improvements in mood and no longer met diagnostic cut-off scores for diagnosis of depression and anxiety.

Depression and bacterial diversity

Before MTT, higher levels of depression were linked to lower bacterial diversity. After MTT, those whose depression symptoms decreased the most had the greatest increase in bacterial diversity, meaning that as bacterial diversity increased, depression symptoms decreased. These correlations between bacterial diversity and depression symptoms suggest that an important link may exist.

Like the previous study, this study had a small sample size and open-label design. Additionally, depression and anxiety ratings were self-reported at only two time points, so as yet long-term impacts are unknown.

Microbiota transfers and future research

Despite the limitations, these two studies suggest that further research is warranted to explore whether MTT may provide a safe and effective alternative treatment. Indeed a search of the clinical trials database shows that across the globe, studies are currently investigating the use of MTT for treating a number of physical, neurological and mental health conditions including: anorexia nervosa, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, Parkinson’s disease, Multiple Sclerosis, obesity, type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

MTT may be an alternative for those who cannot or choose not to use psychiatric medication, or it may be an additional treatment used alongside other treatments.

In summary

The gut microbiome can play an important role in physical and mental health. Increasing our bacterial diversity may improve our mental health and wellbeing. To more extensively change our gut bacteria, we could look at MTT. We do NOT recommend you try MTT at home, but talk to your healthcare professionals. However, we can tend to our inner gardens by increasing our fresh food intake (and reducing processed foods), trying new fruits and vegetables, and enjoying some fermented foods or drinks. Maybe even try making your own kimchi or sauerkraut at home.

Want to find out more?

Check out the following Ted Talks on MTT (and the microbiome) and mental health:

Guilia Enders – The surprisingly charming science of your gut

Mark Davis – Faecal transplants and why you should give a crap

Lisa Kilgour – Microbes, Mental Wellness and Mealtime

Elaine Hsiao – Mind-altering microbes: How the microbiome affects brain and behaviour

Or the following video of Jane who is using MTT to treat her own Bipolar Disorder (Note: Do not try this at home): The Feed – SBS Australia, Power of Poop: Faecal Microbiota Transplants

Note that MTT is also known by other names, including: gut flora transplant, stool transplants, faecal transplants, and faecal microbiota transplant (FMT). The term bacteriotherapy may also be used, however this also includes altering the microbiome using other methods including consuming large quantities of probiotics.

References

1. Singh RK, Chang H-W, Yan D, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. Journal of Translational Medicine 2017;15(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1175-y

2. Smits SA, Leach J, Sonnenburg ED, et al. Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science 2017;357(6353):802-06.

3. Madison A, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: human–bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition. Current opinion in behavioral sciences 2019;28:105-10.

4. Stefano GB, Ptacek R, Raboch J, et al. Microbiome: A potential component in the origin of mental disorders. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research 2017;23:3039. doi: 10.12659/MSM.905425

5. Fond G, Boukouaci W, Chevalier G, et al. The “psychomicrobiotic”: Targeting microbiota in major psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Pathologie Biologie 2015;63(1):35-42. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2014.10.003

6. Hong G. A Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies (Zhou Hou Bei Ji Fang). TingJin Science &Technology Publishing Company, The People’s Republic of China 2000

7. Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom G, et al. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery 1958;44(5):854-59.

8. Leggett K. Coprophagy and unusual thermoregulatory behaviour in desert-dwelling elephants of north-western Namibia. Pachyderm 2004;36:113-15.

9. Hirakawa H. Supplement: coprophagy in leporids and other mammalian herbivores. Mammal Review 2002;32(2):150-52.

10. Chilcott M, Hume I. Coprophagy and selective retention of fluid digesta: their role in the nutrition of the common ringtail possum, Pseudocheirus peregrinus. Australian Journal of Zoology 1985;33(1):1-15.

11. Pannaraj PS, Li F, Cerini C, et al. Association between breast milk bacterial communities and establishment and development of the infant gut microbiome. JAMA pediatrics 2017;171(7):647-54.

12. de Clercq NC, Frissen MN, Davids M, et al. Weight gain after fecal microbiota transplantation in a patient with recurrent underweight following clinical recovery from anorexia nervosa. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 2019;88(1):58-60.

13. Cai T, Shi X, Yuan L-z, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in an elderly patient with mental depression. International Psychogeriatrics 2019:1-2. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000115

14. Kang D-W, Adams JB, Gregory AC, et al. Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome 2017;5(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0225-7

15. Kurokawa S, Kishimoto T, Mizuno S, et al. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: An open-label observational study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2018;235:506-12.

16. Kang D-W, Adams JB, Coleman DM, et al. Long-term benefit of Microbiota Transfer Therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Scientific Reports 2019;9(1):5821.

—

Jessica Heaton is a Master’s student at Te Puna Toiora | Mental Health and Nutrition Research Group at Te Kura Mahi ā-Hirikapo | School of Psychology, Speech and Hearing at the University of Canterbury. Her research explores the use of micronutrient supplementation for treating symptoms of maternal emotional distress; specifically, if this can be used as a safe and effective treatment to protect against adverse birth outcomes that are associated with maternal depression and anxiety.