Disasters, both natural (e.g., earthquakes, floods) and human-made (e.g., terrorism, civil strife), affect communities worldwide, often causing immense disruption and suffering, and lasting psychological injuries.

Living and working in Christchurch, Aotearoa New Zealand has meant we have had our fair share of traumas, but then also the opportunity to study the effect of nutrients on our resilience.

For example, on February 22nd 2011, Christchurch experienced a devastating 6.3 magnitude earthquake that killed 185 people and destroyed the city centre. But as awful as it was, this trauma gave Te Puna Toiora, the Mental Health and Nutrition Lab at the University of Canterbury, the chance to learn whether we could help people recover, not from the physical injuries, but from the psychological ones.

When we are under high stress, we can often reach for foods that are “comforting” (like cookies, donuts, cake, pastries, and chocolate bars), but these foods may not be the best choice for feeding the brain under stressful and demanding circumstances. Comfort foods are often calorie-rich but nutrient-poor.

Further, under high stress (and it doesn’t actually matter what has caused the high stress, whether it be a natural disaster like an earthquake or fire, or witnessing something really traumatic or being stressed because of financial and health uncertainty), the reactions our body goes through can be quite similar. We release adrenaline, an essential neurotransmitter. This is part of our natural alarm response system, the fight-flight response.

Adrenaline enables our body to get us to safety, shut down non-essential functions, and make sure the muscles needed for flight or flight get activated. Cortisol, a hormone, is also essential for the alarm system to function optimally.

Unfortunately, over extended periods of time, the alarm system can go into over-drive, and this is one factor that can lead to re-experiencing memories, flashbacks, hypervigilance, being on edge all the time, feeling anxious and panicky when reminded of the traumatic event, struggling with sleeping and having nightmares.

Making neurotransmitters (like dopamine or serotonin) and hormones (like cortisol) requires micronutrients, which are numerous kinds of vitamins and minerals, like zinc, calcium, magnesium, iron, and niacin. This is a well-established scientific fact. If your body is depleted of these nutrients, then either it won’t have sufficient nutrients to make these essential chemicals, or it will redirect all resources to the fight-flight response (as it is so vital for survival) and there won’t be much left for ensuring optimal brain function to do things like concentrate, regulate moods and sleep.

Consequently, as micronutrients get depleted at a high rate during times of stress, we need to replenish them in greater quantity from our food (and perhaps other sources).

Research from Te Puna Toiora found that following the Christchurch earthquakes as well as other research on stressed communities that B vitamins in particular can be helpful in reducing stress.

In 2019, a terrorist walked into two mosques in Christchurch and killed 51 people while wounding 40 others. Once again our city and its people were dealing with huge trauma.

As an application of translational science, we offered donated nutrients to anyone who was a survivor of the shootings and monitored their symptoms as both an ethical and standard action for good clinical care.

Within weeks, we were clinically monitoring twenty-six people, and we saw the exact same treatment effect that we had seen after the earthquakes and the flood. Not everyone, but many people got better. These clinical observations have just published in an APA journal, International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation.

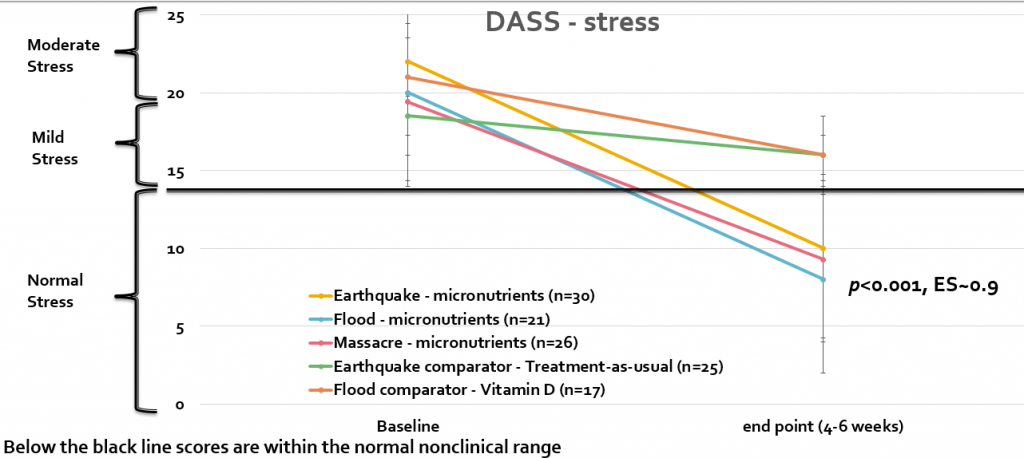

Before starting the treatment, 77 percent of those original twenty-six people we monitored met or exceeded a cut-off score defining probable PTSD. After an average of five weeks, this rate dropped to 23 percent. In other words, of all the people who likely had PTSD, almost three quarters had shown substantial and clinically significant improvement after about a month of micronutrient treatment. Stress reduced into the normal nonclinical range, similar to the controlled research after the earthquakes and a flood (see graph).

Providing survivors with micronutrients appears to reduce psychological distress to a clinically significant degree.

These three different examples of traumatic events illustrate the powerful effect nutrients can have in recovery and improving resilience. Could these results apply to challenges associated with climate change and pandemics? I think so. Anything that can improve our resilience to coping with ongoing stressful events has to be a good thing to know about.

Given ease of use and large effect sizes, this evidence supports the routine focus on eating nutrient dense food and in some cases, additional micronutrients by disaster survivors as part of governmental response.

But the road to assisting these survivors wasn’t simple. In the New Zealand Medical Journal last year, we described how, after the mosque attacks, we faced huge difficulties in disseminating our earthquake and flood research, and the barriers that largely prevented it being translated into practice. We observed an inflexible health system unable to implement evidence-based research, and ethics committees unable to respond quickly in order to facilitate research in the immediate disaster aftermath, when distress and stress is at its height.

Now with these clinical observations showing how easy it is to implement and that the effects are similar to controlled research, leaders can now have the confidence this will be an impactful intervention that will help many. We urge the leaders of our health system to respond to scientific evidence and prepare to translate it into practice after the following disaster. This will benefit everybody – those directly affected, the wider community, health personnel and other services, and the taxpayers and governments who must fund aftermath services.

—

Julia Rucklidge is a Professor of Clinical Psychology in UC’s School of Psychology, Speech and Hearing and the Director of Te Puna Toiora: Mental Health and Nutrition Research Lab.